Mike Diana, born June 9, 1969, is the first American artist to be convicted by the justice system of his country on grounds of obscenity.

To date, he remains the only one to have been judged and charged solely based on his artistic production as a comic book author and illustrator. His trial took place in March 1994 at the Pinellas County Courthouse, in the state of Florida.

At the time, Mike Diana lived with his family in Largo, a small town in Pinellas County, Florida. Since the age of 20, he had been publishing a fanzine called Boiled Angel, which became legendary by force of circumstance. In it, he featured a few little-known artists as well as his own comics. This confidential publication was distributed under the counter and mailed to subscribers.

The young man's graphic productions, drawings, and short stories aimed to expose the most sordid and unsettling aspects of his fellow citizens' way of life. His nervous and unyielding black linework highlighted deviations, particularly of a sexual nature (pedophilia, abuse and mistreatment of all kinds, incest, mental illnesses, especially within religious and familial spheres), that his community seemed to repress and conceal within itself. By pushing insult, desecration, and blasphemy to their limits until their meanings were exhausted, Mike Diana aspired to make Boiled Angel "the most shocking fanzine in America."

In August 1990, the University of Gainesville in Florida was the scene of particularly heinous serial crimes. The bodies of five murdered and raped female students were found on campus, horribly mutilated, with limbs arranged in a macabre staging.

During the investigation, issue 6 of Boiled Angel caught the attention of law enforcement. Investigators believed that the murders bore similarities to some drawings published by Mike in this stapled and black-and-white printed booklet. Mike Diana was searched, and he underwent a DNA test that, of course, exonerated him.

The real criminal, Danny Rolling, was arrested and identified shortly after, but the lead investigator remained interested in the young Mike's case.

Convinced of the intrinsic harmfulness of Mike Diana's work, and ignoring the radical antagonism between reality and fiction that typically structures the human psyche, the police officer sent copies to the Pinellas County prosecutor's office, which then launched an obscenity investigation.

A few years later, Mike Diana was indicted and summoned to court for the publication, distribution, and advertisement of obscene material.

On March 26, 1994, after a week of hearings and four days of incarceration, Mike Diana was sentenced to three years of probation, a $3000 fine, and 1248 hours of community service. He was also prohibited from contacting minors under 18, required to undergo a psychiatric evaluation at his own expense, to take a journalism ethics course and pass, and banned from possessing or producing "obscene material."

He could also be subjected to warrantless searches of his home by government agents authorized to monitor him, seize his drawings, and confiscate his materials. To comply with a requirement later overturned on appeal, he had to submit to urine, breath, and blood tests upon request.

The national-socialist regime in Germany during the 1930s did not treat artists classified as "degenerate art" any differently through its political police. Barely a few years after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, America, now all-powerful, hegemonic, and universal, treated one of its own like a totalitarian state would break one of its dissidents. The "free world," abandoned to its hubris and arrogance, seemed to have renounced its superego. To escape the surveillance and repression mobilized against his art and his person, Mike Diana hid his creation materials in his car trunk and only drew in secret at night.

The First Amendment of the American Constitution, guaranteeing freedom of expression, should have protected Mike Diana from the judicial system's excesses, an instrument misused by the market and opinion democracies that liberal societies had become by the early 1990s, lacking a competing model. But a series of Supreme Court decisions resulting in the latter half of the 20th century that excluded obscenity from constitutional protection — the jurisprudences stemming from Roth vs. United States (1957) and Miller vs California (1973) — allowed judges to interpret the law in a way that made his conviction possible.

Just as the psychiatric institution once attributed "literary pretensions" to Antonin Artaud, the court ruled that Mike Diana's production had insufficient artistic, political, or scientific value to be seriously considered art, thus excluding it from the scope of freedom of expression. Consequently, Mike Diana's drawn work was legally recognized as a crime, and its creator as a criminal.

Despite all the appeals led by civil liberties associations and the support of a few recognized artists, such as Neil Gaiman and cartoonist Scott McCloud, the judgment was never amended. In 1996, the case was presented on appeal, and during the suspension of his probation, before the conviction was confirmed, Mike fled to New York, where he still resides today. The producers of the film dedicated to him in late 2017 (1) ultimately paid all his probation-related legal fees and costs in Florida. After 26 years of judicial persecution, Mike Diana is now a free man.

Mike Diana, who never stopped painting and drawing, has been pursuing his original and powerful work since the age of 18, scrutinizing with an inimitable line, a unique sense of rhythm, and writing style the neuroses and repressions of the American middle class in its most absurd and traumatic forms. His comics speak of everything America wants to hide and suffocate, with a comedic sense and paroxysmal extravagance that make them both exhilarating and disturbing, in an eminently personal and endearing style, halfway between classic comic strips, contemporary art, and outsider art. His original works are exhibited worldwide.

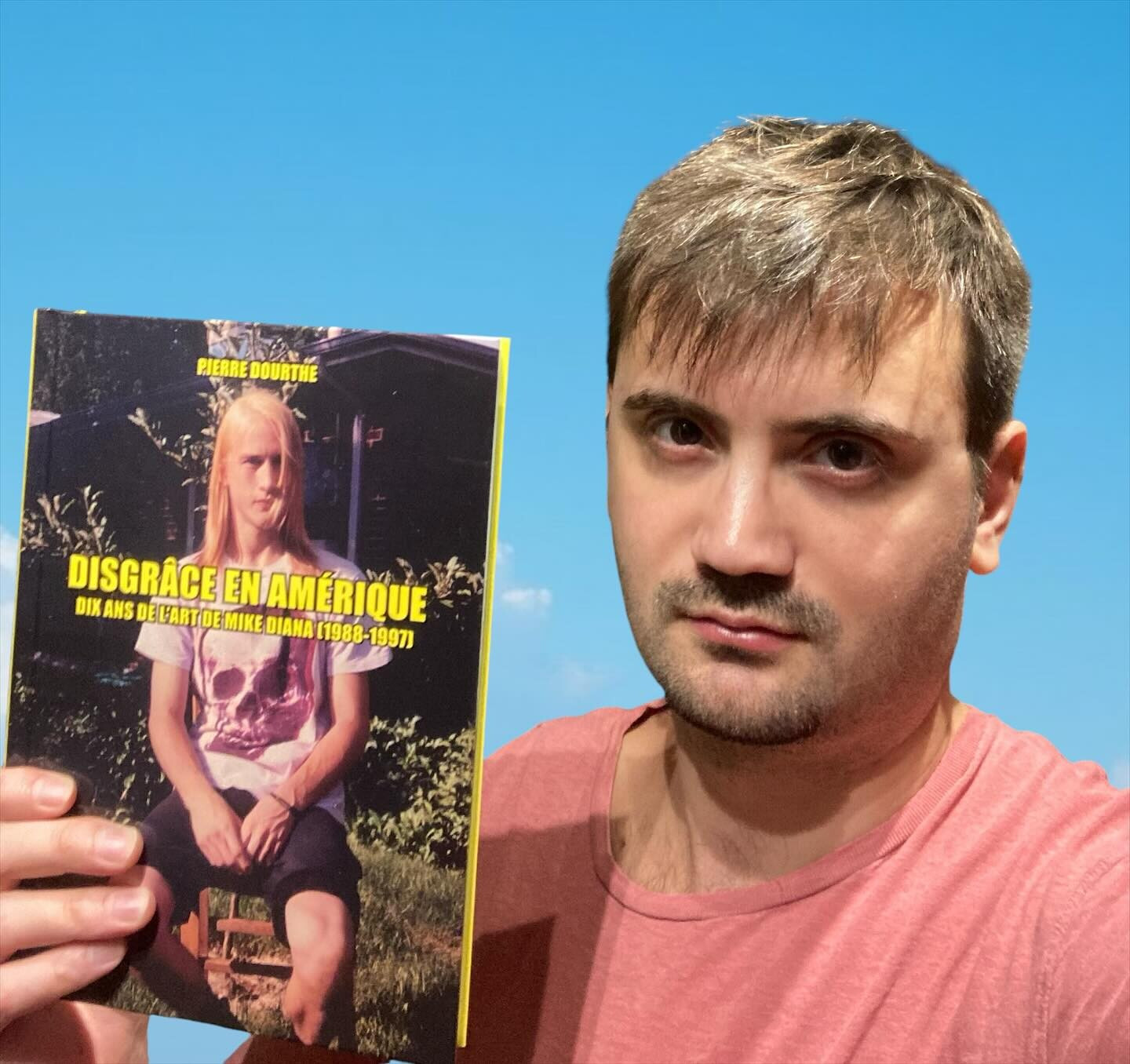

Pierre Dourthe's book, the first French-language work devoted to Mike Diana's oeuvre and journey, offers an aesthetic analysis and in-depth exploration of the phenomenon that revealed America to itself, of the sacrificial logic that led the community to inflict exemplary punishment on the one who, through his sole artistic work, was identified and judged as a threat to social cohesion. It also tells, in a detailed and factual manner, how a puritanical, conservative, and religiously moral America could simultaneously form the matrix of an authentic, transgressive, and incredibly eclectic counterculture that managed to keep an alternative artistic scene awake for several decades, now in complete extinction.

In a country where freedom of expression is recognized as a sacred value, one might have expected the art world, progressive media, and cultural spheres to fervently defend Mike Diana. This was not the case. It appears that, even in the United States and even less so in Europe, the duty to defend an artist, whoever they may be, indicted solely for their works, does not seem to be an absolute self-evident duty for everyone, even among those most directly concerned. The outrage that this absurd condemnation has provoked, both at the time and still today, is not commensurate with the betrayal of the democratic pact committed by liberal democracies in violating one of their cardinal principles. The salutary outburst that seized the crowd in 2015 following the horrific Islamist attack on the editorial staff of Charlie Hebdo seems to be an epiphenomenon whose effects of shock have largely subsided. Transgressions against freedom of expression by the state, its politicized judiciary, pressure groups, community organizations, and the weight of uncompromising and aggressive minorities are multiplying these days against an increasing number of personalities — writers, artists, journalists, intellectuals — without awakening the residual vigilance of a population rendered apathetic, dulled by consumerism, and quick to consider its fundamental rights eternally protected and guaranteed.

Indeed, in a balanced and healthy society, no man can be prosecuted, troubled, intimidated, or condemned simply for drawing, writing, thinking, or speaking. And this, regardless of the form and content of the message he conveys. Freedom of expression is not an abstract slogan or an incantatory notion but an intangible legal principle, particularly mistreated in recent years, whose limits are perfectly defined by the law that simply prohibits defamation, threats, calls for murder, or violence against individuals. It is perhaps the last notion that still radically separates our Western democracies from the notorious authoritarian or dictatorial regimes we so often delight in condemning in the name of our supposed moral superiority. Solzhenitsyn, in The Decline of Courage (2), warned us about the arrogance of our liberal societies and the danger of considering that our principles would be irreversibly acquired.

Ortega y Gasset, in The Revolt of the Masses (3), reminded us how, in the developed world, concerned only with our moral comfort, we had severed all ties of solidarity with the causes of our well-being. "As they [the masses] do not see civilization as a prodigious invention and construction that can only be maintained with great and prudent efforts, they believe their role is merely to demand them peremptorily as if they were birthrights." It is therefore incumbent upon us to cherish and defend them. Is today's America up to the standard of freedom that once justified its international reputation? The question arises with the same urgency for France and Europe. We may be in the process of abdicating what made our way of life desirable in the eyes of the world. Indeed, this book resonates as a call to order.

(1). BOILED ANGELS: The Trial of Mike Diana. A film by Frank Henenlotter featuring Mike Diana, Neil Gaiman, Stuart Baggish, and Luke Lirot. American release in December 2017.

(2). Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Decline of Courage. Harvard address, June 1978.

(3). José Ortega y Gasset, The Revolt of the Masses, 1929.